Diamonds in the Rough

The Development of Public Parks in Providence, R.I.

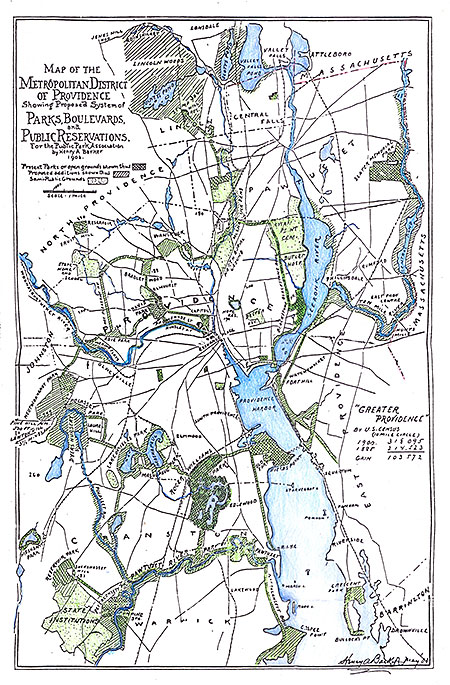

A map of the metropolitan District of Providence, showing proposed system of Parks, Boulevards and Public Reservations for the Public Park Association. By Henry A. Barker, 1903.

Photo courtesy Wendy Nilsson

“The life history of humanity has proved nothing more clearly than that crowded populations, if they would live in health and happiness, must have space for air, for light, for exercise, for rest, and for the enjoyment of that peaceful beauty of nature which, because it is the opposite of the noisy ugliness of towns, is so wonderfully refreshing to the tired souls of townspeople.” ~ Charles Eliot, in the Preliminary Report of the Massachusetts Metropolitan Park Commission, 1893.

We can grumble about how our forefathers mistreated our rivers and open spaces, or we can praise them for having the foresight to preserve pockets of land for public recreation and enjoyment. Public parks are a fundamental component in the fabric of our lives — whether we frequent them on a daily basis, or just have fond memories of little league games — we have all utilized the open spaces created and preserved by our municipalities. Providence in the mid-nineteenth century offered little natural open space for the public to enjoy.

Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Providence more than tripled. Rhode Island was a bustling hubbub of economic vitality. There were over 1,500 factories in Providence making a wide variety of goods, such as textiles, steam engines and jewelry. Although Rhode Island was one of the wealthiest states in the country, it spent less than one percent of its gross domestic income on public spaces. The Metropolitan Parks Commission in Providence saw this as a glaring error in the planning of future development. From its inception in 1891, the Commission argued that for the prosperity of the state and its inhabitants, public spaces must be preserved and maintained.

In addition to open spaces, the health of the rivers and their surrounding buffers was of great concern to the Commission. As the factories’ smokestacks belched smog into the air and the growing urban centers dumped raw sewage down the rivers, the natural environment was slowly degrading. Growth occurred along the “lines of least resistance”, following cow paths through the valleys and level lands. Little planning had been done to provide natural spaces for the growing number of immigrants and it was becoming apparent that the people were growing weary and discontent. Disease and crime rose and it was finally time to pay attention to the future development of farms and remaining open spaces. The Commission argued that city planning must be developed logically and artistically, and that an “economy of foresight” should be demanded.

Open Spaces and the Industrial Revolution

The first public park in the City of Providence was Abbott Park, donated by Daniel Abbott in 1746. It was a mere seven thousand square feet, but would remain the only public space donated by a resident to the city of Providence for another 125 years. In 1871, Betsy Williams donated her 102 acres of farmland and woodland to the City. Even then, the City was hesitant to accept Betsy’s donation, stating concerns that the land was “so far beyond any possible use” due to the swampy low-lying areas. The City’s plan to develop Fields Point Farm on Narragansett Bay as a public park influenced the delay. But the 37 acres owned by the City at Fields Point was not sufficient and abutting property owners and real estate speculators valued the adjoining acreage at exorbitant prices. The fact that part of Betsy Williams’ land was technically in Cranston also hampered the deal. However, Cranston was quick to cede the property, which is now South Providence — eager to relieve themselves of the democratic voting Irish immigrants of the northeastern side of the city.

Providence then set its sights on turning Betsy’s 102 acres into Roger Williams Park. In 1878, Landscape architect, Horace Cleveland submitted his design for the Park. His plan proposed curvilinear roads that followed the natural landscape, with large lakes and strategically placed man-made structures. The other 330 acres of the park we know today were developed in later years.

By 1887 there were still just 121 acres of parkland in Providence split into just eight parks and public lands. The City’s population had surpassed 121 thousand residents — providing just one acre of public space per 1000 people. By contrast, neighboring metropolis, Boston, Massachusetts, had one acre of parkland for every 200 people. At the time, authorities suggested one acre per 100 people was needed for adequate recreation by the public and to reduce crime and disease. By 1915 one acre per 66 people became the standard in America — based on the findings of New York City’s Landscape Architect, Charles Downing Lay.

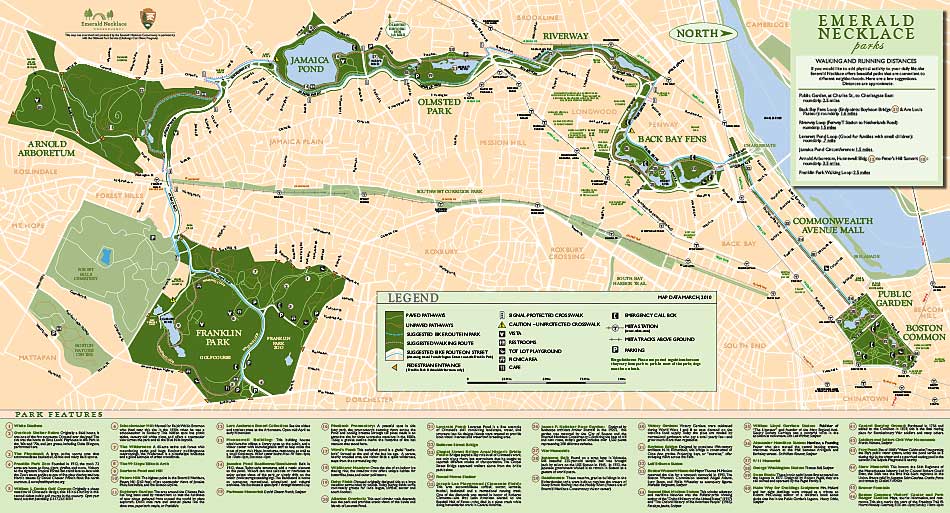

The Emerald Necklace in Boston, designed by Frederick Law Olmstead in 1878, linked several parks, greenways and riverways through a series of walking paths. Drawing off the inspiration of the Emerald Necklace, the Commission proposed a similar system of parks and boulevards for Providence in 1903. Olmstead’s vision of a linear system of interconnected parks was mimicked in the Commission’s design for Providence. Unfortunately, a lack of funds and public interest left the vision on paper only.

A map of Boston’s Emerald Necklace parks as they are now. full size map (pdf)

However, the pressures of urbanization clearly served as an argument for the City of Providence and its surrounding cities to acquire more parkland. The Metropolitan Parks Commission of Providence and the City Council understood this need and identified parcels suitable for parks, playgrounds, athletic fields and recreation facilities. By 1913 Providence had developed and maintained 42 parks totaling 665.5 acres. Roger Williams Park, at 432 acres was already fully developed — leaving just 233 acres spread among the other 41 parks. Population was growing past 424 thousand residents meaning the expanded public land provided one acre per 640 residents.

Providence residents made good use of their parks. As America rolled into the twentieth century, Roger Williams Park was certainly the place-to-be on a sunny Sunday afternoon. Thousands of visitors converged on the Park and could be found boating around the ponds, listening to concerts, attending museum lectures, visiting the menagerie, and enjoying the peaceful refuge. Winter sports were popular in the parks as well. Neutaconkanut Hill provided sledding and skiing and many of the other parks, including Roger Williams Park, offered ice-skating and ice fishing.

The Menagerie and Museum at Roger Williams Park were among the most popular public attractions, drawing thousands of visitors daily. Between 1910 and 1940 generous public philanthropy and large labor supply — both paid and volunteer — created a delightful atmosphere in the parks around Providence, and particularly so in Roger Williams Park.

The Great Depression and the Works Progress Administration

The First World War and Great Depression took a toll on Providence’s Parks as much as they did on the people. Although factories were booming with productivity during the War, peacetime brought production to a halt and the service men returned home to find little in the way of work. Nine years later, as the stock market crashed the economy, the will of the people followed suit. Businesses fought to stay open, schools struggled to continue education with fewer teachers, and school children and adults alike sought free entertainment in the streets and parks.

During the Depression, the parks were filled with children playing and competing in a variety of events to keep them safe from wandering and playing in dangerous streets.

Photo courtesy of the Museum of Natural History, Roger Williams Park.

With no money, the Metropolitan Parks Commission could not maintain the parks and facilities for public recreation and enjoyment. In a time when recreation was so needed for those out of work, Providence sought ways to bring enjoyment and relaxation to their people.

By March of 1933 national unemployment was nearing 25%. The Civil Works Administration tried to provide jobs to the unemployed through small construction projects, but was closed down by July of ’34. In May of 1935, President Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the Works Progress Administration (WPA), promising employment to millions of restless citizens. The Metropolitan Parks Commission jumped at this opportunity, identifying countless opportunities for gainful employment. Between 1935 and 1939, WPA provided more than 4.7 million dollars to the Commission to pay for materials, supplies and laborers — both skilled and unskilled. White-collar professionals, bricklayers, factory workers, artists, and entertainers were provided with meaningful work. In the beginning years of the Depression, national aid was focused on repairing transportation and improving sewage treatment, but as the years went on, parks became a focal point. People were put to work improving the grounds of public spaces, lifeguarding public bathing beaches and swimming pools, overseeing playtime, organizing schedules for baseball, basketball and other sports and providing entertainment in the way of concerts, art exhibits and public theater. Among the many WPA projects in Providence are the construction of the Seal House on Roosevelt Lake and the Oriental Gardens at Roger Williams Park, and the two-mile stretch of sidewalks along Blackstone Boulevard.

The Decline of Public Spaces

The decades following World War II were a time of transition and decline for Providence. As the mills and factories shut their doors, or moved to occupy more spacious and modern suburban plants, the citizens followed suit. Between 1940 and 1980 Providence suffered the largest out-migration of any major city in the United States — losing 28% of its residents and their tax revenues to neighboring towns. Parks and public spaces were among the least of the City’s worries and many were left completely neglected. Crime and vandalism surged in the parks, leaving them a place frequented by delinquents. While Providence was struggling to make ends meet on the needs of the public, people found ways to maintain the public lands they held so dear. Volunteers would plant gardens, clean up trash and debris, and organize public sports and events for the youth.

Revival of Friends Groups

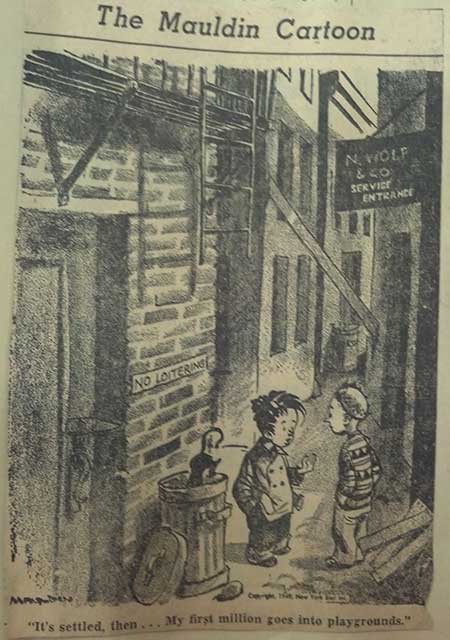

The Mauldin Cartoon in the Providence Bulletin, January 18, 1949, the caption reads “It’s settled then... My first million goes into Playgrounds.”

Photo courtesy of the Museum of Natural History, Roger Williams Park.

Today Roger Williams Park is one of 109 publicly owned neighborhood parks maintained by the Providence Parks Department. These neighborhood parks offer a variety of open space opportunities; from quiet, serene green spaces; to playgrounds, basketball courts and ball fields; to walking trails, nature conservancies, canoe launches and sailing. The City has also partnered with many active neighborhood groups who have helped to expand open space opportunities even further to include the development/ redevelopment of walking trails through nature conservancies, several community gardens, farmer’s markets and a variety of special events and park programming — keeping park spaces active and strengthening community spirit and bonds between neighbors.

There are currently nine park friends groups in Providence, each dedicated to making their neighborhood park a safe and enjoyable outdoor space for children and adults alike to reconnect with nature.

The newly formed Partnership for Providence Parks is available to help any interested parties maintain city parks and public spaces to the highest standards.

Parks are a vital part of a healthy community and keeping them safe, healthy and accessible to everyone is of the utmost importance. Visit your neighborhood parks and experience all they have to offer — you will be glad you did.

A special acknowledgment goes out to the staff at the Museum of Natural History at Roger Williams Park for allowing me to spend hours in the archives researching the history of our Parks. This article would not be possible if the Museum did not have the foresight to preserve the books, prints, photos and journal clippings from our past. Thank you to the dedicated Museum volunteers who sort through the archives making it possible for others to find the information we are looking for!

Article reprinted (slightly modified from the original) with permission from the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program's “Bay Journal.”